Edith's New

Governess

By HandPrince

Chapter 9.

Edith Has Her Dinner

"If you don't

eat your meat," declared Flora firmly, as she

reached across the nursery table and shifted

the bowl of tapioca off of Edith's tray and

out of her reach, "you can't have any

pudding!"

"But Mama doesn't make me-"

"You aren't dining with Mama tonight, my

girl," interrupted Flora. "She has

important guests over for dinner as you well

know, and hence you are dining here in the

nursery with nanny and me. And at

this table, Mistress Fogarty, your

governess' rules apply, not your

Mama's." The child stared at her plate

in glum silence. "You have scarcely

touched your roast ptarmigan," Flora

added. "I shan't permit you to forgo

sound nutrition only to fill up on

sweets. Now finish your meat like a good

girl, and no back chat."

"But Miss Field! It's not f-"

"I said no back chat!" snapped Flora

and silenced the child with a stern

look. Edith sullenly lowered her gaze to

her plate once more but made no move to

eat. Several moments passed as Flora

gave nanny a glance of apology for this

unpleasant interlude during the woman's dinner

time.

Flora had weighed Edith's table manners and

found them wanting ever since her first

evening dining with the Mrs. and Miss

Fogartys. But Flora had avoided

admonishing Edith except for behaviors for

which she had first heard Mrs. Fogarty

admonish the child; and those came only

infrequently. Flora could not risk

the diminution of her authority in her

young charge's eyes sure to follow upon

witnessing her governess overruled by

Mama. And she relished this evening's

brief opportunity to instill better deportment

in the child now that Edith's

governess's authority held

sway at her dinner table for once, rather than

her Mama's.

"I'm not hungry," exclaimed Edith,

sulkily. She had felt hungry when she'd

first sat down with nanny and Miss

Field. But this had been her most

unpleasant dinner in memory, perhaps

ever. Miss Field kept finding fault with

her, ordering her to sit up straighter,

chiding her as unladylike for taking too large

of a bite, scolding her for chewing with her

mouth open when Edith didn't believe she had

done so, and then condemning as 'backchat'

Edith's protestations of innocence in that

regard. And Miss Field had twice

upbraided her for an absentminded elbow on the

table, and once for reaching for the salt

rather asking for it to be passed.

Edith's appetite steadily

waned and her petulant indignation waxed

as found herself repeatedly in the wrong and a

recurrent target of Miss Field's

disapprobation. She hid her anger as best she

could, although this task steadily increased

in difficulty. But hide it she must,

knowing Miss Field quite capable of deeming

certain tones of voice or facial expressions

matters for discipline should they manifest

themselves too obviously. But oh

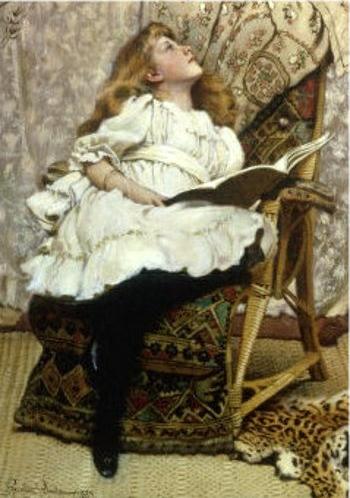

Heavens! A tapioca pudding would taste so

heavenly now and would surely lighten her

wounded spirits!

"Very well then," replied Flora with a

smile, "your pudding shall not go to

waste. I am quite fond of tapioca

actually. Perhaps, nanny," Flora glanced

towards Mrs. Brown, "you and I, shall split

Edith's bowl between us?" Nanny nodded

assent.

"OH!" wailed Edith and exploded from the table

in tears, knocking over her chair in her rush.

She fled through the entrance-way into the

adjoining night nursery, flung herself face

down onto her bed, and gave way to a flood of

furious crying. Crouching in a corner of

her mind lay the awareness that she'd just

been dreadfully naughty. But she'd been

an overfilled balloon - burst asunder by one

final prick. And as her rage, frustration, and

unhappiness poured out into her pillow, the

prospect of a smacking from Miss Field seemed,

for a few moments at least, of trifling

consequence.

Flora excused herself to nanny and rose

to follow.

"That were an awful lot of new rules for her

to learn all at once," exclaimed Mrs. Brown,

with concern, "a few too many perhaps."

"Or perhaps," retorted Flora, regarding the

woman narrowly, "haste is of the essence since

she plainly has a great deal of catching up to

do!"

"That she does, that she does. But there

is only so much one can expect the poor mite

to learn in half an hour."

"I shall be the judge of that," snapped

Flora as she disappeared through the doorway

into the night nursery, ignoring the woman's

parting plea that Flora "not be too severe"

with the girl.

Standing beside Edith's bed in the dimness,

Flora commanded, "Stop! This! Nonsense! At!

Once!" clapping her hands loudly five times to

punctuate each word. Thought

Flora, as she

seated herself on the girl's

bedside,

there can be no gainsaying

the efficacy of hand claps in

winning the attention of a child previously

chastised by those selfsame hands.

The sharp reports of Miss Field's claps, and

her tone, spurred Edith to quickly twist onto

her back lest the seat of her dress prove too

tempting a target for Miss Field's palm.

And she strove to swallow her tears as best

she could. A horrid feeling of dread

rebounded from that corner of her mind in

which it had crouched moments earlier.

Her fleeting courage passed. The

terrible prospect of being turned over Miss

Field's knee now felt every bit as

consequential as ever - fear having all but

replaced fury.

Mrs. Fogarty had informed Mrs. Brown earlier

that nanny was to accompany Edith to the main

dining room after dinner when sent for.

It was Mrs. Fogarty's wish that Edith don her

very best Sunday frock and be made especially

presentable, so as to charm the Earl and

Countess Reddend for a few minutes with what a

well-behaved and pretty daughter the Fogartys

had, followed by her restoration to the

nursery. Mrs. Fogarty hoped to win their

sponsorship for her upcoming charity event to

benefit the village clinic, and would be most

displeased if Edith appeared teary eyed and

out of sorts. And she would likely hold

Flora responsible should that occur.

Flora frowned as Edith dried her

face with the apron of her pinafore and

shifted herself into a sitting position

beside her governess. "P-please

Miss Field! I'm ever ever so so so sorry!"

Edith entreated, taking Flora's left hand in

both of hers and looking up imploringly at her

governess. "I-I didn't mean to be

naughty just now! It just happened!

Please oh please believe me!"

Flora discerned

at once that Edith spoke truly.

Still, naughtiness is naughtiness even when it

"just happens," as tantrums so often do.

Under normal circumstances Edith would be

receiving her spanking now as remuneration for

her ill-mannered outburst. But

circumstances were far from normal.

Flora had no desire to spoil the impression

her employer wished to make upon the Reddends

by sending Edith swollen-eyed, distraught, and

obviously freshly-smacked, to be presented to

the Lord and Lady below. But she also

had no intention of allowing Edith to discern

this fact, lest the child look for ways of

twisting such disciplinary hesitancy on

Flora's part to Edith's advantage in future.

Miserable with suspense, Edith

stammered out the question foremost in her

mind. "Miss Field... a-are you," she

tried to swallow, failed, then continued, "are

you... g-going to whip me now??" The

child's shoulders hunched with anxiety and her

small frame shuddered slightly as she uttered

those last words. Her gaze fell from her

governess's eyes to her governess's lap.

Regarding Edith sternly, Flora feigned

indecision. "That depends," she replied

slowly in an ominous tone, continuing to

regard the child sternly, as if mulling over a

weighty decision as yet unsettled. Edith

took a breath and opened her mouth preparing

to speak, but Flora silenced her with a finger

across her lips. "You may not speak

until you are given permission!" Edith

hung her head again and silently upbraided

herself for having gotten herself into this

parlous circumstance.

"Edith, look at me." The child

raised her gaze to Flora's. "At table,

did you decide beforehand, 'I shall run from

the room without asking to be excused because

I wish to be willfully naughty,' and then you

did so?" Edith emphatically shook her

head from side to side, uncertain if she was

permitted to speak yet. "Or, on the

other hand, did you act before you had a

chance to think?" An emphatic up and

down shake of a little head followed.

"So you weren't wilfully naughty, and that is

to your credit. Still, your misbehavior

just now exhibited an absence of self

control. No one possesses the virtue of

self control at birth. It must be

instilled in children... by means of discipline!"

Flora allowed that portentous word to hang in

the air for several seconds as Edith squirmed

with unease. "For your lack of self

control," lied Flora solemnly, "I'm rather

inclined to put you over my knee and spank

you good and proper!"

By the light through the open doorway leading

back to the day nursery, Flora noticed with

satisfaction tiny glistening specks of

moisture beginning to appear on Edith's

forehead. Since a spanking isn't truly

an option, thought Flora, a bit of wholesome

fear must suffice in its stead. "But

perhaps," continued Flora,

as if newly viewing the question from a

fresh perspective, "that

might be overly hasty." She took Edith by her

hand and rose from her bedside. "Come

with me."

Edith followed Miss Field back into the day

nursery and to her place at the table.

Miss Field explained that Edith would now have

another chance to show she had sufficient self

control so as not to warrant a dose of

discipline. Edith nodded silently, still

wary of Miss Field's earlier admonition not to

speak unless given permission. And how

could she ask for permission to speak without

first speaking, and thus risking being deemed

willfully disobedient for doing so??

Miss Field explained that Edith would

demonstrate her self control by finishing

every bit of her roast ptarmigan. Edith

regarded her plate, and found it a loathsome

sight. Her meat had gone cold, and Edith

had never liked ptarmigan even when it was

hot, at least not how Cook prepared it, in a

greasy onion sauce which had now

congealed. But,

like a slavering wolf standing over a

cornered rabbit, the

frightful possibility of yet another smacking

across Miss Field's knee loomed ever present

in her mind. So Edith steeled herself to

her task. She took bites as large as she

dared take without risking making Miss Field

cross, and swallowed each as quickly as she

could with a minimum of chewing.

As Edith undertook her assigned exercise in

self control, Flora contemplated the child's

general conduct in the days since her

introduction in the master bedroom to that

novel use of Mama's hairbrush. Flora had

felt then that Edith's chastisement had

concluded prematurely, without fully thawing

the icy hardness of disobedience in her young

heart and thus bringing forth the warm

softness of compliant repentance. And

Flora now deemed herself vindicated in light

of the child's subsequent misbehavior and

attitude. A quick learner when it suited

her, Edith had rapidly gained insight over the

past fortnight regarding just how much Miss

Field would allow her to get away with,

without quite crossing the line and earning

herself a chastisement.

Nanny and Miss Field silently exchanged

glances as she methodically cut pieces off her

slab of meat and in short order transferred

them to her mouth and then to her stomach,

until at last every bit was gone.

"That's my good girl," cooed nanny, relieved

that Edith appeared to be out of

trouble. Miss Field appeared to relax

somewhat as well. Perhaps, Edith

wondered, might I be allowed my pudding

now?

But suddenly even tapioca pudding didn't seem

appetizing any more. Indeed, with a

growing sense of alarm Edith realized she had

better not put anything else into her stomach,

as her urge to vomit gradually grew. If

only she were permitted to speak! She

hoped her nausea would pass, but instead it

just grew steadily more urgent. Edith

realized that she would have to visit the

water closet and soon. But she had

already narrowly escaped a smack bottom that

evening for rushing from the table without

asking to be excused, and she dared not repeat

that selfsame infraction now. But how

could she ask to be excused without disobeying

Miss Field's command not to speak until given

permission?! ?

"PleasemayIbeex-" Edith covered her mouth with

both hands and rushed towards the bathroom,

her stomach spasming violently. Some

vomit had already squirted between her fingers

by the time she reached the water

closet. Closing her eyes, she removed

her hands from her mouth and gave her tummy

liberty to convulse at will. Two long

heaves came in close succession, followed by a

shorter one after she'd had an opportunity for

several deep breaths. The emptiness of

her stomach came like a blessed relief.

But with a stab of fear, Edith felt a hand

upon her shoulder. Had Miss Field come

to give Edith her smacking now??

The hand drew her close and Edith, eyes still

closed, immediately recognized the familiar

smell of nanny. "There there, my lamb,"

the old woman cooed, "let's get you out of

your pinafore before it soaks through to your

frock." Edith opened her eyes, and held

her arms aloft to let nanny remove the

garment, which Edith now saw had splatters of

sick down its front. Nanny placed the

soiled pinafore in a bucket from along the

wall and placed the bucket under the tap to

fill and allow the garment to soak.

Still seated at the table, Flora pondered this

fresh turn of events. Had Edith truly

been sick? Flora suspected she very

likely had, but wasn't entirely certain.

If Edith had stealthily induced vomiting with

a finger down her throat, she wouldn't have

been the first little girl in Flora's

experience to play up in such a manner.

Perhaps this was a case of girlish

histrionics, Edith's stratagem for getting the

better of Flora and undermining Flora's

discipline program? Although she doubted

it, Flora, wishing for certainty, rose and

entered the bathroom.

Edith clung tightly to nanny and began to cry

heavily as she saw Miss Field enter.

Edith couldn't remember a time in her brief

life when so much had gone so terribly wrong

in so short a time. And was she to be whipped

now by Miss Field?? Oh, it was simply too

awful! The little girl clung to nanny

with all her might, her small form shaking

with deep heaving sobs.

Mrs. Brown met Flora's gaze steadily as she

entered. Before Flora could speak, the

woman said, "if you're wondering if this child

is just joshing, I can tell you for a fact she

is not. I've known her since the night she

were born. And that's a good deal longer

than you I daresay. So if you're about

giving this little one a smack bottom, I won't

allow it, not unless the Missus herself tells

me to stand aside I won't."

Just as Flora had again begun to think Mrs.

Brown as merely a sweet empty-headed old lady,

another side of the old woman reemerged, a

side which Flora had encountered just once

before while trying to compel Edith to take

her cold bath on Flora's first day as

governess. The woman's eyes as she

steadily met Flora's gaze possessed a subtle

glint, faintly feral, like unto a mother bear

vigilantly watching over her cub. Flora

inly bristled at this challenge to her

disciplinary purview, but maintained an

impassive countenance.

Flora had more than enough experience with the

ploys and subterfuges of discipline-dodging

little girls to recognize Edith's flood of

tears as nothing of that nature - simply the

sorrow of a child in the midst of an

uncommonly trying day. No interrogation

was necessary. "I entirely agree, Mrs.

Brown," declared Flora in a clipped tone,

meeting the woman's eyes. "I hadn't the

slightest thought of giving Edith a smacking,"

lied Flora. "I merely entered to discover if I

could be of any assistance to you."

Nanny's visage softened. "Well you can

ring for the scullery maid to clean the sick

off the floor for a starter." Flora did

so. Then came a knock on the nursery

door, which Flora opened to reveal one of the

footmen, (thankfully not Randy), announcing

that the lady of the house requested the

presence of Mistress Fogarty and Mrs. Brown in

the main dining room. Flora replied that

Edith had had a "mishap" and bade the man wait

out in the hall, assuring him of the imminent

emergence of the two personages he sought.

Back in the bathroom, Edith sat on the side of

the bathtub and let nanny bathe her face

repeatedly in cold water to conceal the

evidence of her recent tears, and with a wet

cloth, clean away splatters

of sick which had fallen onto

loose strands of the girl's hair. Then

she dried the wet spots with a clean cloth and

was giving the child's hair a thorough

brushing when Flora came back in.

Edith had been crying too hard

to hear nanny's earlier words to Miss

Field; she had only been aware that nanny

had spoken something. The little

girl glanced warily at Miss

Field as she reentered, but most of her

earlier fear had faded. If Miss Field

intended to give her a smacking, she likely

would have done so ere now. Hence Edith

deemed herself probably safe.

"It's an awful shame," mused Mrs. Brown aloud

to Flora as she continued to brush, "that here

we be, sitting in the midst of the greatest

empire that ever there was, where the sun

never sets. And some little girls," she nodded

at Edith, "have so much, while right here in

Behrendshire we have other little girls that

barely have anything to wear." Flora,

still concealing her displeasure, agreed that

this was indeed a sorry state of affairs, and

expressed her hope for its prompt

rectification.

"Since

you asked if you could be of assistance," the

woman continued, "on top of the wardrobe

nearest the hearth is a heap of whites which

this one," she nodded at Edith, "has outgrown

just a wee bit. When you have time, will you

be a dear and take them to the missionary

barrel for me?" With a glance at Flora

and a subtle smile bespeaking words left

unspoken, the woman added, "surely some poor

lassie just a wee bit smaller than this one

shall put them to good use?" Feigning

inner reflection, she added, gazing off at no

direction in particular, "why... perhaps you

yourself might know of some deserving little

mite fitting that very description?"

Naturally, Flora agreed at once. Mrs.

Brown's obvious intent to place these items

into Lily's possession somewhat softened

Flora's displeasure towards the old woman, but

without resolving Flora's irksome sense of a

score yet unsettled. Before she could

examine the items, though, a knock came at the

nursery door. "You rang, Miss?" asked

Helen Reid. With her bucket and mop in

one hand and her scrub brush in the other, she

had arrived prepared for whatever chore might

await her above stairs.

Flora directed Lily's mother to the spatters

of vomit on the floor. Just after the

scullery maid entered the bathroom and began

filling her bucket, Mrs. Roberts emerged

therefrom, accompanied by brand spanking clean

Edith.

"Edith," declared Flora, "your Mama, nanny,

and myself, all need you to be on your very

best behavior when your Mama presents you to

the earl and countess. Is that

understood?" Edith nodded inattentively,

this being perhaps her half dozenth iteration

of this selfsame admonishment from one adult

or another. "When you return, you will

make your ablutions, undress, and go to bed at

once. You shall have no further food

until your breakfast tomorrow." Edith nodded

again. She felt not the least bit hungry

and deemed this punishment as trifling as a

"smacking" from nanny's arthritic hand.

"Now now, Miss Field," protested Mrs. Roberts,

"isn't that a wee bit too-"

"Mrs. Roberts!" snapped Flora, "I'm afraid I

must remind you that my decisions are and

shall remain paramount in the realm of

discipline for Mistress Fogarty. I shall

therefore thank you never to interfere, or in

any such matters to set your will against my

own!" Before the woman could answer,

Flora continued, "and I would strongly advise

you not to involve Madam as you earlier

insinuated you might do. Mrs. Fogarty

has no patience with members of staff

bothering her about their disputes with one

another. And furthermore, she hired me

precisely on account of my experience and

efficacy as a disciplinarian, in part I

daresay, due to her perception of yourself as

deficient in that regard!"

The old woman's lips tightened with anger and

she met Flora's eyes coldly for several

seconds, then looked down at Edith.

"Well then, my pet," she said gently, "we'd

best be getting ourselves to the dining room

shouldn't we, before your Mama is cross with

the both of us. Wait for me in the hall,

there's a good girl."

Edith dropped a hurried curtsy to her

governess and disappeared out the nursery

door, relieved to be out of Miss Field's

view. Now a new danger loomed.

What if she said or did the wrong thing in

front of the titled guests? Mama would

be frightfully cross with her if she

did. And would she send for Miss Field

to chastise her??

Back in the nursery, the nanny set to work

placing each of the three dinner trays onto a

low table by the doorway for a footman to

retrieve, while pointedly

ignoring the governess. The latter,

deeming herself victor in that last exchange

of words, turned to the wardrobe and began

sifting through the heap of items destined for

charity. There to her satisfaction lay

an assortment of little petticoats of various

styles, camisoles which could double as

nightwear, knickers, and drawers, all of which

appeared ideal for a child of Lily's

stature. She barely noticed Mrs. Roberts

opening and then closing the bottom drawer of

the dresser on the other side of the doorway.

The nursery door closed behind Mrs. Roberts,

to Flora's relief, leaving herself quite alone

save for Helen, now finishing up with her

mopping. "Just doin' me job is all,"

Helen muttered when Flora thanked her.

"Helen, I wonder if you would be so kind as to

do me a further service?" Helen sighed

wearily and stood, awaiting her new orders in

silence. Flora beckoned her to the

wardrobe, presented her with the heap of

clothing, and asked, might she take this to

the missionary barrel? or better yet, to a

certain little girl of her acquaintance in

need of such items? Helen frowned and in

a hard tone responded, "I can't be a-do'in

nought as might get me the chuck wi'out no

reference! Not wi' winter a-comin' on and no

place to go for me-" her tone softened with a

hint of anxiety, "or me Lily."

Flora assured her that nanny had the authority

to set these items aside for needy little

girls and that Helen would commit no fault for

conveying them to Lily. And in the

unlikely event of some trouble from the

Missus, Flora pledged to take full

responsibility and to testify most

emphatically to Helen's blamelessness in the

entire matter. Helen looked to Flora, to

the garments, then back again,

twice. Her steely expression gave

way at last to a faint smile. "Well I'm

powerful grateful to ye' then. An' me

lil' nipper 'll be powerful chirpy 'bout it as

well, I'm bound!"

Helen took the garments under her left arm

which held her scrub brush, excused herself

and turned to go. "I appreciate you

taking this chore off my hands, Helen," Flora

remarked. "As you can imagine, I

shouldn't wish to run into Randy in an empty

hallway!"

Helen turned in surprise. "'Aven't you

'eard? Got the sack 'e did! Mr.

Carlson said 'e were on-" Helen paused for a

moment, "on 'approbation' 'e called it,

on account of Randy a-botherin' the kitchen

maids and a-puttin' 'is 'fingers where'n 'e

oughtn'. I s'pose 'e 'spected ye were so

unpopular-like that 'e could do wi' ye as 'e

pleased." Flora thanked the maid

effusively for this welcome news. "Good

riddence to 'im I say," continued Helen.

"And there's several younger maids as used to

talk ill o' you who now won't 'ear one word

spoke wrong against ye', Miss Field. Ye'

did that boy right they say - gi' 'im just

what 'e long deserved, you did. And so say I!"

Once Helen had taken her leave, Flora, flushed

with pleasure at how well this evening had

turned out, sat herself at Mrs. Brown's desk

and began to write.

Edith descended the stairs slowly, her hand in

nanny's, doing her best to help steady the old

woman. Nanny's other hand gripped the

balustrade as she painstakingly negotiated

each step. Edith hoped Mama's

requirement of her presence in the dining room

would not prove lengthy. Miss Field had

ordered her put straight to bed afterwards,

but hadn't said Edith mayn't have a

candle. The prospect of herself in one

of her satin nightdresses, curled up under

covers rendered toasty by nanny's bedwarmer,

and with her copy of "At The Back of the North

Wind" before her, seemed a most inviting port

in her storm of this unhappy evening.

Back in the nursery, Flora completed the

following note for the nanny:

[it ran]

My dear

Mrs. Brown,

As

I ordered previously, Edith is to be put to

bed straightaway upon her return from the

dining room. Her candle is to be

extinguished and she is not to have games,

toys, or amusements of any sort accompanying

her to bed. Please convey to her that

she is forbidden from asking you for any

food until her breakfast upon the morrow;

and caution her that should she do so I

shall treat that as a serious breach of

discipline, the consequence of which she

well knows. Her restrictions shall

conclude upon taking her breakfast.

[signed]

Miss Field

"Good evening, my Lord," intoned Edith just as

nanny had instructed her, lowering her eyes

and dropping her daintiest curtsy before the

Earl of Reddend. He smiled oddly,

looking her up and down with keen interest,

and nodded. Seated at the dining table

at the place normally occupied this past

fortnight by Miss Field, the earl didn't

impress Edith as a particularly grand fellow

despite his fine clothes and title.

Short in stature, his ruddy face was wrinkled

with age, his nose appeared swollen, and his

breath smelled of brandy. Edith

pretended not to notice when he patted his lap

and beckoned her to sit thereon, as she

crossed around to the seat she normally

occupied, and dropped an identical

curtsy. "Good evening, Lady Reddend."

"My goodness what a perfectly charming child

you are," replied the countess with a

smile. She was closer to Mama's age than

her husband's, but not quite as pretty,

thought Edith, who couldn't tell if her breath

also smelled of brandy or not, on account of

the woman's cloying perfume. She wore a

splendid cream-coloured gown, festooned with

what appeared to be tiny diamonds. "Your

first London season is not as far off as you

likely imagine, Miss Fogarty," continued the

woman, affably, "you shall be presented at

court and shall curtsy to the Queen herself,

as you doubtlessly know. Do you look

forward to that day, my dear?"

"Yes, my Lady," answered Edith, although in

fact she had truly given the matter little

consideration, since her first London season

did indeed seem to lie in a dim future epoch,

despite the woman's words.

"My compliments to your governess," the woman

declared, "clearly she has taught you well in

the manner of curtsying to your betters."

"I already knew how before she

came along!" blurted Edith, displeased at

hearing Miss Field receive undue credit of any

sort. To Edith's right, Mama shifted in

her seat and Edith at once realised herself at

fault. "But," the little girl continued

hastily, "my governess gives me a great deal

of practice!"

"And if she in the least measure resembles my

governess at your age," laughed the woman

merrily, "I daresay she gives you something

else if you don't curtsy when you ought

to! Am I right?"

Edith felt herself begin to blush once she

caught the woman's meaning, feeling rather too

embarrassed to reply. "Edith?" said Mama

in a tone of warning. Mama's meaning was

clear. Ignoring a direct question from Lady

Reddend was plainly forbidden.

"I must curtsy when meeting her and when

taking my leave and when passing her in the

hallways. Should I ever forget she

promises me a smacked bottom," replied Edith

mechanically, resentful at being forced to

divulge such information to a stranger, but

hiding this emotion with great care.

"But," she added with fresh animation, "I have

never once forgotten, so she hasn't ever

smacked me for that."

The countess's smile disappeared as she

regarded Edith skeptically.

"Never? Are you certain you aren't

telling a falsehood, my girl?"

From across the table, her husband leaned

drunkenly in Edith's direction and declared

with half serious, half jesting solemnity,

"Every liar shall have his portion in the lake

which burneth with fire and brimstone," then

chuckled to himself.

Edith's indignation swelled. She wanted

to stamp her foot as hard as she could and

shout at both of them that she was not a

liar. But of course she held her breath

instead and strove to conceal her anger.

Thankfully, Mama came to her rescue.

"Our Miss Field is Edith's very first

governess. And she has been in our

employ for scarcely a fortnight. So I

have every confidence Edith is not

dissembling."

"Then I am glad of this news," replied the

countess to Mama, her smile returning.

To Edith, she continued, "I daresay I find thoroughly

dismal the thought of such

a darling girl as yourself being smacked."

"Yes, Madam!" piped Edith, leaping at the

opportunity to concur with the woman upon a

sentiment with which Edith so wholeheartedly

agreed.

"Has your governess any severer

punishments for you then smack bottoms?"

Edith found this question baffling. How

could Miss Field possibly punish her with

greater severity than by giving her a

spanking??

"Edith?" chided Mama, "Lady Reddend asked you

a question."

"No My Lady," replied Edith to the countess,

then, "did your governess smack you?"

hoping to shift the focus of this particular

line of conversation to some other little girl

besides herself.

"Edith!" scolded Mama gently, "don't ask

impertinent questions!"

Lady Reddend waved aside Mama's concern and

answered, "Yes she did indeed... when I was fortunate."

Edith regarded the woman with

bewilderment. Had she misspoken?

Had Edith heard her incorrectly?

"A proper smack bottom when necessary never

did a child any harm," continued the countess,

as much to the other adults present as to

Edith. "I didn't enjoy them of course,

no child does. But they were over

quickly. And I generally deserved

them. But when she would lock you in the

dark closet for hours with only water and a

few leftover crusts of bread, that was quite

another matter."

"Locked? For hours?" asked the astonished

Edith. "But... what if you had

to...to... visit the water closet?"

"You simply didn't!"

"But..." Edith struggled to think of a

decorous way to pose her urgent question,

"what if you... what if you just couldn't...?"

Sensing the child's meaning, the countess

replied with a sigh, "in that case you were in

disgrace and you got a birching?"

"What is a

'birching?'" With mounting horror, Edith

listened as Lady Reddend explained the nature

of a birch rod and its use. Across the

table, Lord Reddend, whose chin now rested

upon his sternum, began to snore. "Does

a birching hurt... as much as a smack bottom,

Lady Reddend?"

"Oh dear me, child, far far worse! The

soundest of smackings is the merest trifle

compared to a birching. So count yourself

fortunate to have a far kindlier and less

strict governess in your Miss Field than I had

in mine. On some

occasions my governess left me bloody. "

Fearing being seen as impertinent, but unable

to contain herself, Edith frowned and

remonstrated, "Nanny says I mustn't ever say

that word, that it is terribly rude."

The countess laughed and smiled warmly at

Edith. "What a darling little innocent

you are! No my dear, I didn't swear just

now. I meant her rod sometimes broke my

skin and drew a bit of blood." Edith's

horror redoubled. She knew of brutal

treatment of children, albeit mostly in

books. But she'd never imagined that

such barbarities could befall little girls of

the better classes such as young Lady

Reddend... or perhaps... Edith herself??

With Lady Reddend apparently done with her

reminiscence, and Edith quite at a loss for

words at her realization that the countess

viewed Miss Field as a soft, lenient

disciplinarian, an awkward silence fell for

several seconds.

"Lord Reddend," exclaimed Mama, loudly enough

to bring the man sputtering back to

wakefulness, "was your recent shooting party a

success?" Sputtering awake, the earl began to

expound upon the shortcomings of his

gameskeeper and blame the man for the

declining pheasant population on the Reddend

estate. Mama, her hand below the view of

her guests, discretely signaled nanny.

The woman slowly rose from her inconspicuous

seat in the corner, took Edith's hand, and

unobtrusively led her away.

As they began to mount the stairs, step by

step, again holding the old woman's hand to

help support her, Edith asked, "was I good,

nanny?"

"Good enough, I'd wager," replied nanny

curtly, intent upon climbing stairs rather

than conversation.

Gaining the top of the stairs, Edith released

nanny's hand trusting her to walk the

remaining distance to the nursery by Edith's

side unassisted.

As Flora began her descent of the

back stairway, she paused. It crossed

her mind that in view of Helen's news of

Flora's newly elevated popularity among at

least some members of staff, perhaps she might

consider taking the front stairs and braving

the bustling kitchen and dining area?

She would save a considerable number of steps

should she do so.

But Flora couldn't deny that Cook intimidated

her. Flora may have gotten the better of

that woman once. But she preferred to

forego a repeat engagement, especially in the

very midst of Cook's domain.

Edith stepped past the green

baize door into the nursery and heaved a deep

sigh as she at last felt herself out of

danger. Only her bed and her book lay

before her. But no sooner had she begun

to luxuriate in this cosy sense of safety then

she suddenly realized she was hungry -

ravenously so. Nanny stood by her desk,

reading a sheet of paper.

"Nanny I'm dreadfully hungry!" she whined.

"That you are," the woman replied with a deep

sigh of her own, "but there's nought to be

done about it til the morrow - Miss Field's

orders. Complaints never filled an empty

belly, my girl, so let's hear no more of

that." She led Edith into the night

nursery. "And let's have you out of your

frock, then."

Edith lifted her arms high and permitted nanny

to undress her layer by layer, and then get

her into her nightgown. Perhaps, she

hoped, her book might soon distract her from

the grumblings of her tummy. As Edith

quickly washed her face and hands in the

basin, Nanny disappeared back into the day

nursery and returned shortly afterwards with

the warming pan full of fresh glowing

coals. Slipping the hot metal round and

about between Edith's sheets for half a minute

or so, she motioned for the child to climb

into bed. Nanny had warmed her bed

nicely, as she always did, and now only one

thing remained.

"Nanny, light my candle so I can read,"

commanded Edith.

"You're to have no candle and no reading -

Miss Field's orders. Get you to sleep

now and when you wake up perhaps it will be

the breakfast trays arriving that wake you."

Edith burst into tears of self pity and wailed

into her pillow while nanny, ignoring her,

undressed and donned her own nightgown as the

child gradually cried herself out.

In times past, when cajoling Edith to finish

the contents of her plates, nanny had on

occasion besought Edith to think of the

starving children in India, to which Edith had

been wont to retort that nanny could jolly

well send it to them then, which generally

ended that line of conversation. (In the

most recent instance, though, and the only one

since Miss Field's arrival, nanny had become

cross and threatened to report Edith to her

governess for "cheek"). Starving

children had never been more than a vague

amorphous concept in Edith's mind - until

now.

Edith couldn't manage more than a few seconds

at a stretch without urgent thoughts of food

again crowding her mind. Those poor

children! It felt this dreadful just to

be tucked into bed with no dinner; but how

must they feel having nothing for days

and days? or even weeks? Edith's

imagination could not encompass such

suffering.

Instead, she fixed upon suffering such as her

imagination could encompass, albeit barely

so. She pictured herself locked in the

inky blackness of the closet of Lady Reddend's

cruel governess, desperate to visit the water

closet, but forbidden, and with no idea if

release from her prison lay near or far in

future. And then she imagined the worst

- her battle not to soil herself, lost - lying

in the darkness amidst her stench and filth,

knowing that she was now "in disgrace" and

would surely be whipped with a perfectly

horrid birch rod until her bottom bled.

Miss Field's methods did indeed seem soft and

lenient in comparison.

Upon opening her apartment door, Flora gasped

with delight at the sight of Lily's freshly

made gingham frock and lacy pinafore laid out

side by side on her bed. Now she should

have the pleasure of presenting them to Lily

when the child arrived for her nightly visit.

Nanny had begun extinguishing the candles in

the day nursery. The light through the

doorway dimmed with each until it failed

completely and only starlight through the

windows remained. The wind had risen,

rattling the panes slightly in their

frames. Never before had this familiar

sound seemed to Edith so forlorn and

desolate.

From the darkened day nursery came the sound

of a drawer pulled open, then closed again,

followed by nanny's footsteps. Her dark

shape appeared in the doorway briefly then

vanished in the gloom as she proceeded further

into the room.

To Edith's surprise, nanny didn't climb into

her own bed, but sat down on the side of

Edith's and silently guided her to a sitting

position. Into Edith's hand she pressed

something smooth and cool, which Edith

recognised after a moment as the base of a

ceramic bowl. Taking hold of it with her

other hand as well, she brushed against a

spoon whose handle clinked against the bowl's

rim.

There, as she drew the bowl near her face,

came the aroma of tapioca pudding.

|